As stock markets  have continued to flirt with highs not seen since before the great financial crisis of 2008 and the heights of the dot com bubble before that, there has been a recurring discussion of the “light volumes” that have taken markets to these highs. A lot of airtime has been spent trying to figure out where the traders who are “supposed to be” there actually are. When people say things are “supposed to be” a certain way in the markets is usually when you need to raise some red flags.

have continued to flirt with highs not seen since before the great financial crisis of 2008 and the heights of the dot com bubble before that, there has been a recurring discussion of the “light volumes” that have taken markets to these highs. A lot of airtime has been spent trying to figure out where the traders who are “supposed to be” there actually are. When people say things are “supposed to be” a certain way in the markets is usually when you need to raise some red flags.

It is a well-known belief amongst traders that volume is a sign of conviction – the more participants believe a certain condition to be true, the greater the reliability of the move. Of course it is near impossible to know the absolute number of participants acting on a certain belief, and so proxies like price or volume serve as indirect measures of investor sentiment. Like any ‘rule of thumb’ in the markets, however, it is valuable to take a closer look at the charts to see whether or not this ‘rule’ holds water.

What do the numbers say?

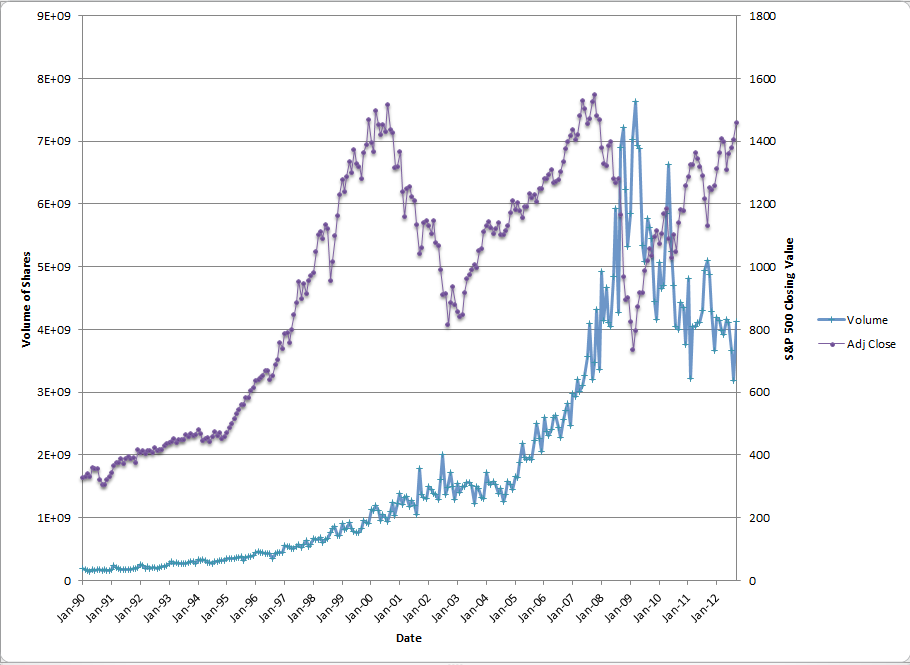

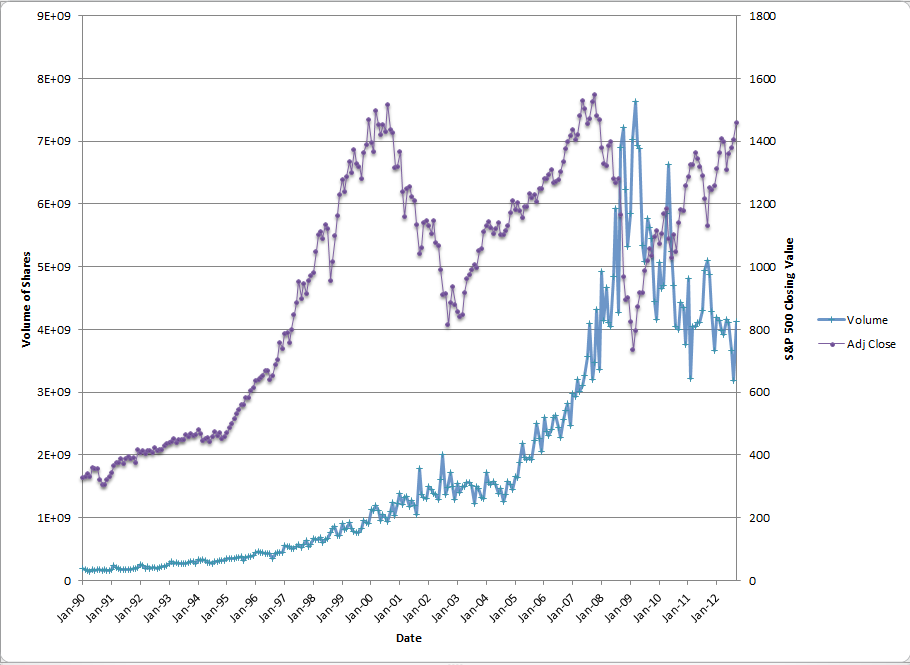

We pulled data from the S&P 500 for the last 22 years and plotted the monthly closing price of the S&P 500 index against the volume of shares traded. One of the most startling things that jumps out is the huge surge in trading volumes that took place from between 2006 and 2009 where monthly volumes shot up from between 1-2 billion shares/month from 2000 to 2006 to a peak of between 6.5-7.5 billion shares per month between 2008 to 2009. Why were there so many more shares being traded? It could be any number of factors from increased frequency of trading (i.e. same number of participants but more frequent trading) or greater numbers of participants or both. Examining why is a bit beyond the scope of this article, but some simple points to ponder can be gleaned by overlaying the volume of shares traded with the performance of the S&P 500.

First, with sharp moves down in price, volume moves sharply higher – this happened noticeably from mid-2000 to late 2002 (bursting of the dotcom bubble) as well as between early 2008 and early 2009 (financial crisis). Second, in the large moves up in the markets between early 1995 and mid-2000, as well as from 2003 to 2008, a good portion of those initial upward moves happened on relatively stable or “boring” volume. What is possibly perplexing about the move up from the early 2009 lows is that this rise in prices has been happening while trading volumes have been in relative decline. Of course the large number of shares traded happened during times of heightened enthusiasm or extreme pessimism.

Keep calm and carry on

While difficult to draw any firm conclusions, greater “emotion” tends to bring with it parabolic shifts in market participation. If more participants are ‘bullish’ about the market, we see surges in volume and price, and likewise if we see sharp drops in the price there is also a sharp spike in volume as traders duck for cover. What is interesting in the most recent run up is the absence of emotion in volume, indicating that perhaps it is the more level headed participants that have been at work in the markets while the emotional buyers are either licking their wounds or too uninterested in participating or both.

As we near the previous highs in the S&P 500 index, on either light or abated trading volume, the market history might offer up the important lesson that it is possible to see sizable moves up in the market price even in times of “boring” volume (case in point AAPL as it crossed the $700 threshold). It may be difficult, if not impossible, to determine what the “normal” level of volume in absolute terms is or should be, especially given the “new normal” of algorithmic and high frequency trading, as well as greater presence of discount brokerages, lower trade commission rates for trading and low interest rates. Nonetheless, the “vanishing” trader(s) might very well be the emotional crowd – who for now, it seems, have all opted to line up for new iPhones instead of boring old stocks.

Defining a market is as simple as picturing a boxing ring with two opposing opinions representing the fighters. One of these opinions places a bet on an increasing value of a share price while the opposing side wagers that the share price will decrease in value. This is the simplest way to visualize the market: a boxing match with buyers in the blue corner and sellers in the red corner. The most important aspect to understand is that both sides cannot win. For every winner, there is a loser and this simple premise is what creates a market.

Defining a market is as simple as picturing a boxing ring with two opposing opinions representing the fighters. One of these opinions places a bet on an increasing value of a share price while the opposing side wagers that the share price will decrease in value. This is the simplest way to visualize the market: a boxing match with buyers in the blue corner and sellers in the red corner. The most important aspect to understand is that both sides cannot win. For every winner, there is a loser and this simple premise is what creates a market.